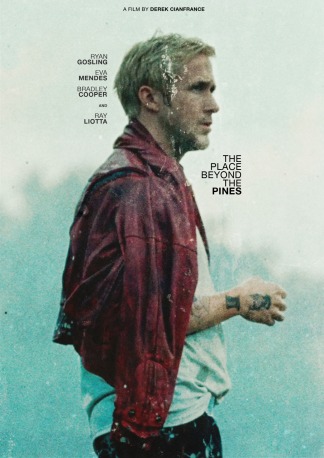

Before “epic” became bro shorthand for some major stunt or accomplishment, it was defined as “a long poem…narrating the deeds and adventures of heroic or legendary figures or the history of a nation.” The Place Beyond the Pines stands appropriately as a traditional epic, tracing the generational sins & legacies of fathers and sons. Starring Ryan Gosling as a heist man on two wheels this time, it’s the yin to Drive‘s yang.

Gosling’s Luke Glanton is a dirt bike stuntman with a traveling circus who finds out he knocked up the the young Romina Gutierrez (Eva Mendes) on his last pass through Schenectady, NY and now has a one-year-old son, Jason. Luke’s heart is clearly in the right place; motivated by is own absent dad, he fumbles around trying to figure out how to step up to fatherhood. Things get more fraught as he spars with Romina’s current beau Kofi (Mahershala Ali), who embodies the ideal father figure, literally putting a roof over Romina and baby Jason’s head.

Challenged to provide for his boy, Luke finds work with the quirky, kind mechanic Robin (Ben Mendelsohn, in one of his best performances), and soon the duo start pulling bank heists using Robin’s brains and Luke’s wheels. Luke’s impulsiveness gets the best of him, and the fallout from their actions demands a future reckoning.

Director/writer Derek Cianfrance effectively taps into an emotional reservoir that makes The Place Beyond the Pines stronger with age and repeated viewings. The film could easily have been an updated version of The Town: Now on Motorcycles, given the crime genre framework and Gosling’s profile as a hearthrob, but in the film’s commentary track Cianfrance says he’s not a fan of the ego filled swagger of things that are “cool:”

“I hate cool things. I like warm things. I think coolness is so next to coldness and that’s next to death. I think warmth is next to life. So, anything that can kill cool, in my movies is, or in my life, is what I want.”

The film adheres to this ethos of emotional honesty and un-coolness in ways that ring true to each of our lives. It’s a credit to Cianfrance and his actors that they make Pines into a Shakespearean family tragedy that could bleed if you pricked the screen.

Cianfrance pits the bleach blonde kid from across the tracks against the hero cop from a well-connected family, and both come out looking equally maladjusted in a way that delicately plays with the class spaces between them. This is no neat cops-and-robbers morality tale, but a story about the messiness of people and their universal drive to be accepted, to be forgiven, to be loved. The narrative unmasks its characters, revealing people coping with moral failures that reverberate through time and generations. Epic indeed.

Visual stylings form the backbone of this ambitious meditation on history and place: a shot of Luke blissfully motoring down winding roads is re-stated and re-framed later, when his son bicycles down a similar stretch of asphalt. A father and son have a tete-a-tete in the backyard pool, only for the next generation to be ignored in the same spot. The film reminds us that place has a memory that extends before and beyond us, and sometimes those memories repeat or refract as they play out again.

This visual tone poem is enhanced by a haunting soundtrack comprised of Mike Patton’s original compositions and pieces from the likes of Arvo Part and Bruce Springsteen, literally under-scoring some of the best montages in recent memory. The music highs make you feel like you’re gliding through the sunshine with Luke; the tonal lows make you feel like you’re in purgatory. Given Cianfrance’s Catholic background, it’s not surprising that the film’s climactic music evokes an almost Biblical horn of judgment as the buried past comes back to demand payment. Sight and sound work together to evoke uncanny echoes of history and family.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Cianfrance and Gosling would come up with a film so richly textured and emotionally nuanced after their initial work on Blue Valentine, the indie hit about a marriage dissolving before our eyes. Cianfrance wrote 37 drafts of Pines‘ script, and despite the heaviness of the drama, it strikes a grace-filled note that feels well-earned.

When Pines was released it didn’t earn much attention, maybe because folks came in expecting another iteration of Drive – a neon synth fantasy of masculinity, dripping cool from every frame. Yet Pines has aged well, deserving more praise and love than when it arrived. Drive goes for your id, The Place Beyond the Pines goes for your heart.

– Remington